“Charlie’s good tonight in’nit he?” — Mick Jagger, Madison Square Garden, 1969.

Charlie Watts’s drum kit was a pitch-perfect reflection of the man who sat behind it for The Rolling Stones for nearly 60 years: modest yet essential.

Charlie famously eschewed rock drum solos as frivolous, show-offy expressions of ego. A lifelong jazz devotee and a keen student of elegance, economy, and swing behind the set, Watts liked to think of his six-decade tenure as drummer for one of the world’s most celebrated and enduring rock bands as his day job. It was a gig that enabled him, ages ago, to indulge his childhood dream and desire to lead jazz ensembles and play the music that really mattered to him.

Not that the Stones’s music didn’t matter. Far from it.

Yes, there is the amusing anecdote of a pre-dawn Watts shaving and getting dressed in an impeccably tailored Saville Row suit and knocking on a hotel room door in the 1980s to confront an effusively inebriated Mick Jagger — who had rung Watts’ hotel room demanding know where his drummer was. Within a few seconds, Charlie established, unequivocally, that Mick had got it the wrong way around. The legendary Stones frontman was actually his singer. The declarative moment came, according to guitarist Keith Richards, who was there in a similarly celebratory state, in the form of a snappy right hook from Watts.

Yes, he loathed living out of suitcases and being on the road for increasingly endless tours, which he once famously summed up as “five years of playing and 20 years of waiting around.”

But when pressed, Watts confessed why he had stuck around for thirty albums that spanned a dozen U.S. presidential administrations. There was one simple reason, the same one that kept his marriage to his wife, Shirley, intact for 57 years: Loyalty. “I play the drums,” he said, “for Mick and Keith.”

Over the years, Charlie Watts was the elegantly burnished flip side of the gaudy Glimmer Twins’ coin. His quiet temperament and gentlemanly manner proved to be a sensible, grounded contrast to the more mercurial Mick, Keith, and troubled band founder Brian Jones, who died in 1969. (Longtime Stones bassist Bill Wyman, who retired from the group in 1993, was the band’s other early introvert).

Charlie was, at least by all public appearances, bashful and reclusive, with little use for superficial celebrity culture. He was utterly unconcerned with musical trends or fleeting fashion except for his own tasteful panache, stylishly refined over the years. In his later years as a rock elder statesman, Watts was even named one of the worlds’ best dressed men in magazine polls he likely never saw.

As the iconic stage personas of the preening peacock Jagger and epically debauched Keith became quintessential ’70s rock star blueprints — and then grew, for better or worse, to gargantuanly cartoonish proportions — Charlie remained seated in the shadows. Cool, calm, and collected, as the tune on “Between The Buttons” goes. (With an art school background in graphic design, Charlie provided the back cover artwork for that 1967 LP, as well as teaming with Jagger to design the Stones’ increasingly elaborate stage sets in the ensuing decades).

Through all of the stylistic and musical reinventions, transgressions, and transformations wrought by changing times and eras, Charlie refused the makeover.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-963703-1330742257.jpeg.jpg)

Musically, Watts kept a sturdy, unfussy beat with a minimum of rolls and fills and a predilection for a propulsive, sharply cracking snare drum, accented with well-timed cymbal crashes. He famously followed the cue of guitarist Richards’ rhythmic lead and pacing, which gave a subtle tug on the Stones rhythm section, and infused it with a sense of space and looseness. The result was time-keeping just a wee bit behind the beat (“sloppy” is the not-entirely flattering term sometimes employed to describe that effect). But that’s what made the magic. I hear the Stones backbeat as ineffably, raggedly right. It’s part of the band’s alchemy and signature. Often imitated, never duplicated.

Of course, I wasn’t aware of any of this stuff when I first fell for the Stones sound, discovering them on a chunky blue eight-track tape of “Hot Rocks” at my best friend’s house after school one afternoon in 1980. He was a young drummer like me and had his uncle’s behemoth Big Band Slingerland set up in his bedroom. After swooning for the mop-topped Beatles at age ten (they had already been broken up for three years), I felt a musical vacuum in my early teens at the tail end of the ’70s. They were empty years of radios filled with hot air that blew in from the corporate rock programming of the day, and larded with poodle-haired loverboys who named their bands after continents.

But popping that tape into my friend’s player may as well have been like unwrapping a Willy Wonka bar and discovering a glittering gold ticket hiding inside the wrapper. In a single euphoric instant, my entire life changed. I can still feel the thrilling effect of the taut guitar riff and swooping bass run that opened into the tremendously exciting, percussive jangle and chug of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” I was all in. Gobsmacked and besotted. How can I accurately describe it? Have you ever fallen headlong in love at first sight? Yeah. It was like that.

My teenage ears opened wide, providing eager passage to my head, gut, and loins. All at once, the groove of the Stones’ musical universe — sexy, swaggering, sneering with youthful insolence — set in motion a seismic shift in my perception and perspective, and perhaps most importantly, my own sense of self. As if sending me a secret message — Attitude Is Everything — the Stones gave me a degree of internal confidence in moving through the world.

With the Stones lighting up the corridors of my consciousness — throwing electric switches and leaving their stealthy footprints up and down the halls of my mind, I no longer felt as awkward or unsure on the inside (the outside was another matter). On the contrary, I felt shaken awake to newly hatched, albeit tenuous possibility. Their sound was everything I longed to be.

For me then and now, that sound was, is, and will forever be the pure distillation of what my idea of elemental rock & roll was and is: a glorious gumbo that began with blues, the early rock & roll rhythm architects (Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley), tough and earthy R&B, and even gospel. But there was something more to my fascination, why it felt so perfect.

The Stones were, at first, skilled imitators of the form; skinny English white boys barely out of their teens, pledging allegiance to heavy Black American music. This wasn’t lost on me, a fledgling imitator striving to find my voice and be cool too. They had the hubris to worship — and remake themselves into — something they weren’t. And from that deep, dirty clay, they conjured something original and distinctly theirs: unruly, perfect rock & roll.

Charlie Watts was a big reason for my devotion to that sound. To an amateur, adolescent drummer like myself, Watts made his instrument — and the heady Stones music I was now devouring — approachable, accessible. Doable. The implicit message Charlie sent with his playing was that with a lot of practice and a little luck, even those of us who weren’t unattainable rock gods like Keith Moon or John Bonham could possibly play drums for a world famous rock & roll band someday. Or at least a very good one in our town or city.

Unlike those headline-grabbing drummers with outsized personalities who, thanks to their ego, virtuosity, vices, or some combination thereof, vied with their band’s lead singers or guitar players for adulation, Charlie was supremely unperturbed by the spotlight, or the lack of it. Actually, he shunned attention and actively rebuffed the limelight (and how freaking cool is that?).

Instead, he was all business, content to be an anchor holding down the beat, but driving it unmistakably too, with surprising, deceptive force. Check out tracks like “Get Off of My Cloud,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Rocks Off,” or “Beast of Burden,” just to name a few among scores of tracks Charlie put his subtle yet indelible stamp on over the years. Arguably as much as Jagger or Richards, the flair of his contributions helped punctuate the personality of those songs.

Then there’s the man himself. I was always intrigued by Charlie’s long jaw and droopy demeanor (“I’m not bored — I just have a very boring face,” he once quipped) which, to me, augmented his stoic bearing and anti-rock star stance. Then there was his droll sense of humor when he did speak, or conceded to a rare interview. And let’s not forget the bemused eye-rolls he gave to the camera-mugging frontline as they indulged in what he no doubt considered silly rock star antics in the band’s early music videos.

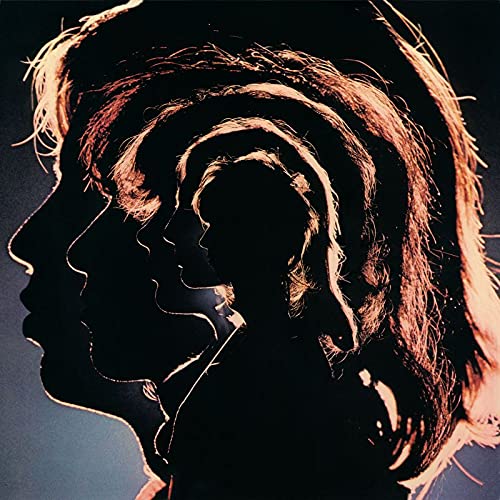

But Charlie also had his moments of mirth. There he was, in a rare moment of (possibly forced) euphoria, clad in Mick’s stage-worn Uncle Sam top hat from the 1969 U.S. tour, weilding a pair of electric guitars and leaping (in glee?) next to a drum-donned donkey on a deserted airstrip on the cover of 1970’s seminal live album, “Get Yer Ya Ya’s Out.”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1151061-1347950480-7973.jpeg.jpg)

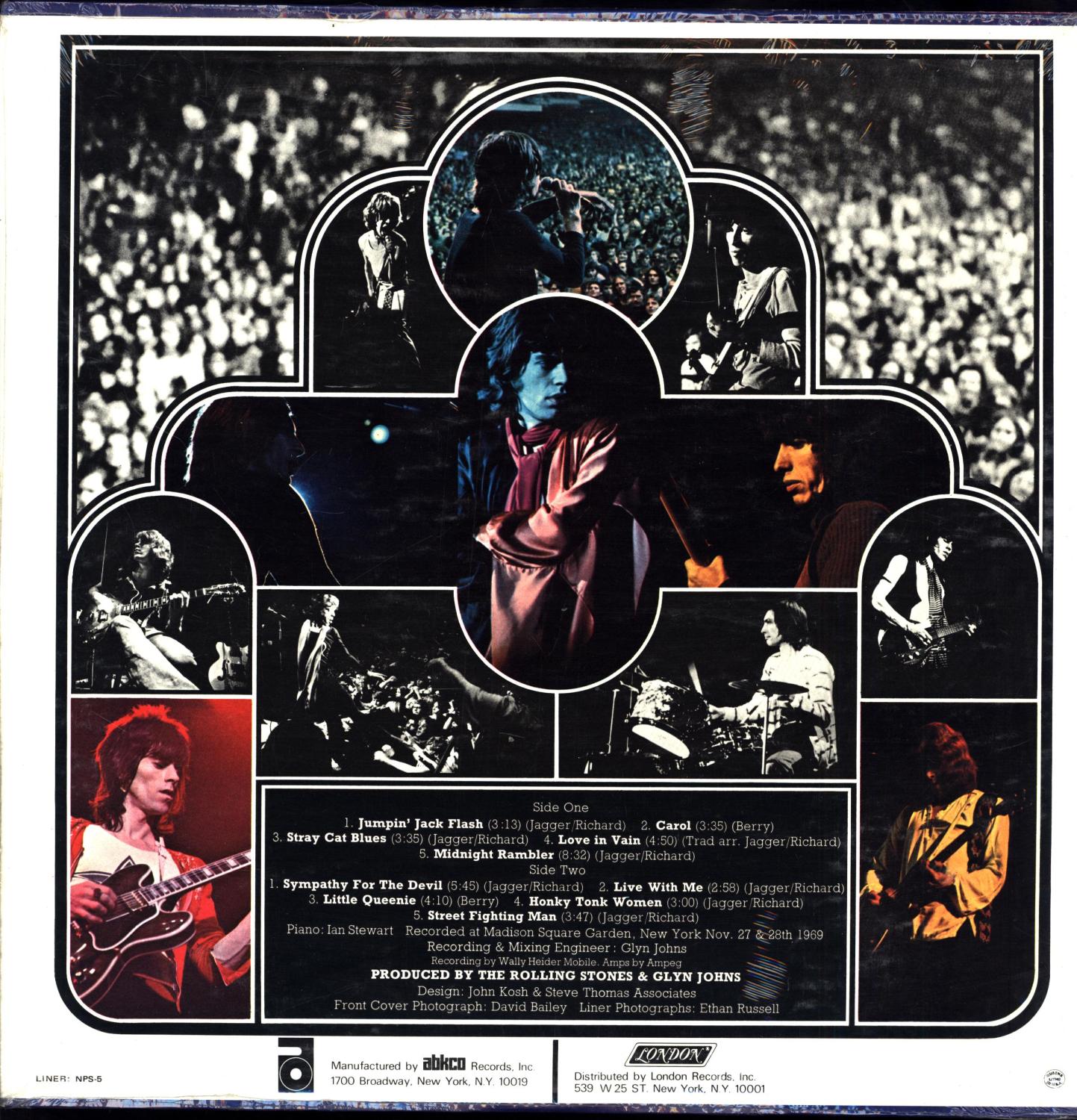

I remember saving up to buy that LP second-hand at my local used record shop on a snowy winter’s day and getting a fizzy feeling of anticipation as I sat clutching it in the passenger seat of my mom’s silver 1977 Plymouth Volare while momentarily held hostage on some supermarket errand. I couldn’t wait to get home and play it on my crappy Zenith hi-fi. Hell, I could practically hear the amplifiers humming already.

I gazed with concentration at the back cover art panels depicting each band member. Tucked into a small frame on the right side, there was Charlie in black and white, working behind his oyster pearl finish Gretsch drum set, his blurred sticks striking cymbal and tom. He conveyed a steady sense of calm amid the propulsive swirl of movement around him. To me, he looked a bit like an old-fashioned railroad engineer, feeding coal into a freight train furnace to keep the locomotive moving. Tellingly, Keith Richards has also described Charlie’s role on stage that way. In the photo, Watts is wearing a slight smile of, dare I say, satisfaction.

The frozen moment of that winter’s day in the car returns whenever I listen to “Ya Yas.” And the Stones as a sonic scrapbook of memory has been a lifelong constant for me. None more so than last weekend, as my brother and I drove from our childhood home to the train station two hours away in Boston amid a hot summer sun. It had been an emotionally fraught 72 hours.

We had attended a poignant memorial service for my older sister, who had been claimed by cancer the year before at the far-too-young age of 63. We had also spent time reminiscing with our once-hearty but now fading 97-year-old mother (the same mom who drove that silver Plymouth with me in tow some 40 years before).

The night before our morning drive back to the distracting bustle of our lives, my brother and I had stayed up very late, playing “Exile On Main Street” loud on a boom box set on our family’s old oak kitchen table. The familiar, reassuring blast of “Exile” was a welcome balm. I felt a little less helpless with the Stones at my side. At one point, I chuckled and observed that, on the raunchy swamp-groove of “Ventilator Blues,” Charlie’s pungent fills were as close as he’d ever allow himself to an actual drum solo.

The sad news flashed on my phone barely eight hours later, as we were halfway home on the highway: Charlie Watts, Rolling Stones Drummer, Dies At 80. Within minutes, close friends began to text me condolences, as though he too were part of our family whose mortality I had been confronting and contemplating. “That’s a hard one,” my brother said, staring ahead over the steering wheel. “Charlie’s been with you your whole life.”

Something grabbed in my throat. Indeed, the Stones had marked so many milestones, had been the soundtrack to so many of life’s pivotal, private moments. From the first one when I was 16, playing along to “Honky Tonk Women” on the drums and imagining I was Charlie. To just last night, at age 57, reaching for the noisy solace of “Exile” in the dark.

Now, hurtling toward the station in the sobering light of a day freighted with such awful news, time suddenly seemed to be speeding up and, like that black highway, passing underneath us, far too swiftly.

Great piece of writing. Being a drummer myself, although not espcially a Stones fan, I of course regret Watts his death. But then: drummers don’t really die. They donate themselves to the rythm of life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words, and nicely said. If anything, drummers are about energy! Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece! Really captured his personality, style, and musical presence. The story bought back a lot of great memories of the 70s and 80s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“That’s a hard one,” my brother said, staring ahead over the steering wheel. “Charlie’s been with you your whole life.”

My mother-in-law, who I have known for 21 years, was a busy woman. You practically had to make an appointment with her; the only time she was available was on Sunday afternoons after church. She has lived a very full life. Now she is in hospice. I have not cried for her because I watched her cram every waking minute into exercising, donating, quilting, bowling, chauffeuring older friends, traveling, and marveling at her boundless energy. A life well-lived, the way she wanted it.

And when I heard the news about Charlie a week ago, I burst into uncontrollable tears for an hour.

I thought: There must be something wrong with me; here I am, crying for a person I’ve never even met, and I can’t cry a single tear for my husband’s mother: I am NOT right.

But, after calming down, I realized, like your brother said, that I also had known Charlie my whole life. He – they – have always been there for us. I know more about this man than I know about some of my own family members. I realized that we are among countless millions of people around the world who were listening to that same soundtrack as we grew from children into adults, mourned, took lovers, suffered breakups, contemplated our futures. These men ARE family members to us. Thanks for this article Jonathan Perry, it allows me to feel that I AM right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing these wonderful insights and perspective (and, thanks for reading…I cried for Charlie too). Beautifully said, and sending good thoughts to you and your family. So heartened to hear about a life well and fully lived, as your mother-in-law has undoubtably had. I know it can still be hard to watch such a vibrant life dissipate. Our mom has just entered that hospice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Watts becomes a lens for a stunning reflection on life and mortality here. Very moving with–dare I say it?–its own propulsive rhythm. Thank you, as always, for capturing the musical moment as no one else can.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on RPM: Jonathan Perry's Life in Analog and commented:

On the occasion of the late, great Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts’ birthday.

LikeLike