In the more than half a century since their inception, demise, and rebirth, the Memphis-bred rock band Big Star have been revered as everything from anachronistic power pop avatars to iconoclastic cult legends making introverted music in an extroverted era. So iconoclastic were they, in fact, that Big Star actually had to break up to make their masterpiece.

Perhaps just as improbably, that masterpiece, “Radio City” – issued to terrific reviews yet scant commercial sales – was feted last year with a slew of sold-out shows and an international tour to mark the 50th anniversary of its 1974 release. Which makes perfect sense, since it’s a prescient work whose melodically and lyrically bittersweet approach has influenced generations of alternative rock and pop artists, from the Replacements to Teenage Fanclub to Fountains of Wayne and beyond.

Helmed by Big Star’s lone surviving original member, drummer-singer Jody Stephens, the anniversary outfit dubbed the Big Star Quintet included Mike Mills (R.E.M.), Chris Stamey (the dB’s), Jon Auer (the Posies), and Pat Sansone (Wilco, Autumn Defense) – all of whom grew up fervent Big Star fans. Auer has been a charter member of Big Star’s latter-day lineup, off and on, for 30 years. For shows already scheduled for next spring and beyond, the quintet will have Teenage Fanclub’s Norman Blake on board, replacing Wilco’s Sansone, whose day job bands presumably keep him busy.

“These guys do their homework – that’s the secret,” says Stephens on the phone from Ardent Studios in Memphis, TN., where Big Star recorded its similarly acclaimed 1972 debut, “#1 Record,” as well as “Radio City,” and the final, fragmented effort known as “Third,” belatedly issued in 1978. “Everybody has this innate sensibility about these songs, and they play them with the right spirit.”

In lesser hands, summoning that spirit would be a tricky, even impossible, task. Both of the band’s principal singer-songwriters, Chris Bell and Alex Chilton are gone. Bell, who quit the band after “#1 Record,” died in a car crash in 1978 at age 27. Chilton died of a heart attack at age 59 in 2010 after leading a reconstituted Big Star with Stephens in the ‘90s and beyond. Also departed is original bassist Andy Hummel, who died of cancer four months after Chilton, also at age 59. Still, Stephens describes the current incarnation’s connection with modern audiences as “enormous.”

“We’ll never have Alex up there on stage and that’s as sad as it gets,” Stephens allows, wistfully. “Nobody’s ever gonna deliver these songs like Alex, with his touch. But we all love the music and that’s what counts. Everybody takes it to heart.”

There was always something special about Big Star, whose magical, nearly mythological aura has kept their sparkling, harmony-and-heartache-laced music alive and fully present. Myriad reissues of their trio of ‘70s evergreens– not to mention box sets, high profile covers culled from their catalog (Cheap Trick’s reworked version of “In The Street,” for instance, served as the theme song for the long-running sitcom, “That 70s Show”), and a 2012 documentary entitled “Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me” – have certainly helped ensure that enduring exposure.

It wasn’t always that way. The band initially called it a day after the hopefully titled “#1 Record” failed to make a commercial dent. Despite stellar reviews, poor distribution by Ardent’s parent company, Stax Records, a Southern soul label in flux, ensured the record couldn’t be easily found in record store racks. (Sadly, the same fate would eventually befall “Radio City” two years later). A disheartened Bell, who had been battling personal demons and clashing with co-leader Chilton over the band’s direction, quit to regroup and focus on a solo career. Meanwhile, Stephens and Hummel, both still in college, concentrated on finishing school. Chilton continued writing songs, but was at loose ends.

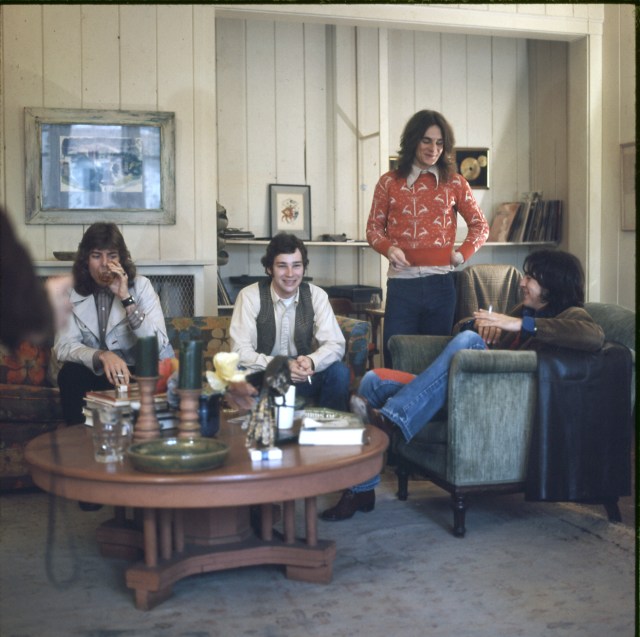

Then came an unlikely catalyst for Big Star’s return: the loftily named National Association of Rock Writers Convention of 1973, essentially a Memorial Day blowout shrewdly invented and hosted by Ardent as a way of luring the most influential national rock critics of the day to Memphis to eat, drink– and see and hear a reunited Big Star first-hand. The gambit worked like a charm.

“Everybody had a great time, and that was the first time we played to a real Big Star audience, where everybody liked the music and celebrated it with us,” says Stephens of the pivotal show featuring the newly stripped-down trio of Alex, Andy, and Jody. “It certainly gave me a lot of confidence moving forward. We were off and running!”

Bolstered by the fresh start, the trio headed back into the studio with the band’s biggest champion, Ardent owner and producer John Fry, to work on the new material that would become the beloved “Radio City.” Fifty years on, its unique charms flicker and flash like a colorful kaleidoscope of shape-shifting sounds and angular stylistic turns.

Notably, the album contains what would become the band’s signature song, “September Gurls,” an autumnal anthem to inchoate longing and soul-deep friendship. But there’s also so much more: the sweetly “Rubber Soul”-esque acoustic daydream of “I’m In Love With A Girl”; the ruminative ballad, “What’s Going Ahn”; the adolescent escapism found in “Back Of A Car”; and one of Stephens’s favorites, the rousing “O, My Soul”, which kicks off the record with a 47-second instrumental blast of rhythmically ropey, syncopated funk.

“If that’s not a clarion call for excitement,” Stephens says with impish delight, “I don’t know what is!”

Touring the album’s 50th anniversary felt surreal, Stephens said, but it’s a sensation that stretched back to his days manning the drum kit as a very young man. “It was hard to believe I was even a part of Big Star, getting to play with Alex and Andy and hearing the songs they were coming up with – I was a lucky guy. I had no idea about longevity, nor did I ever think about it, really. There was just the ‘here and now’ excitement of it all.”

Even a half-century on, the material still feels fresh to Stephens. He doesn’t approach playing it as nostalgia, nor does he perform from a kind of distance: namely, a dramatically changed perspective brought on by life experience; an older musician revisiting a young man’s passions.

“No, I don’t have a different relationship with (the songs),” Stephens says. “But I’ll say that back in the ‘70s, the only time I really practiced was playing with the band. So being able to come in and do an hour (of rehearsal) every day, I step on stage now with a lot more confidence. I gotta admit, there are pluses about both. There’s a real nervous energy if you aren’t prepared that can be really cool. But there’s also a real determined energy when you are.”

Call it focus or control, but no matter how well-rehearsed this band is – and make no mistake, they are indeed a polished and joyfully potent unit of seasoned pros – what cuts through is the exuberance and emotional resonance, then and now, of these evergreen songs.

“When you’re 19, 20 – emotions run high at that age, and boy, it was all emotional for me at the time,” Stephens continues. “These songs connected completely with me, along with the melancholy of Alex’s voice, the melodies, the edgy quality of it being a three-piece.”

As for the particular alchemy that gave Big Star its exceptional essence? That’s an elusive proposition to pinpoint. “Whatever happens once you hit the ‘record’ button,” Stephens says, “is hard to explain to anybody.”